MADE MAN

Feb. 26, 2013

Just 14,000 people live on the 84 square miles of Johns Island, home to Williams Knife Co. Known for Civil War reenactments and the Johns Island Presbyterian Church, this small South Carolina hamlet is gaining fame for award-winning blades favored by Davis Love III and Michael Jordan. And the man behind them is part of a movement that is redefining craftsmanship in the United States today. For our second Budweiser Black Crown “Backstage Pass” Q&A, we asked company founder Chris Williams about switching from investment banking to knife making, shucking oysters and shucking office jobs.

–

You never know when the last knife order might come in, so I put all I can into each and every one.

–

MADE MAN: Let’s start with the obvious—what made you become a knife maker? CHRIS WILLIAMS: My grandfather was a knife maker out of necessity. He was one of 13 kids in a poor, rural farming family in North Carolina. He learned the craft in a very crude manner, but he was very good at it and he taught me. I finished my economics degree at the University of South Carolina, moved to Charlotte and worked in investment banking for 13 years. One day I just went to work and said, “This isn’t very fun anymore.” I always liked making knives and I’m an outdoorsman. By Christmas 2009 I had a bunch of orders for knives and decided to do this full time.

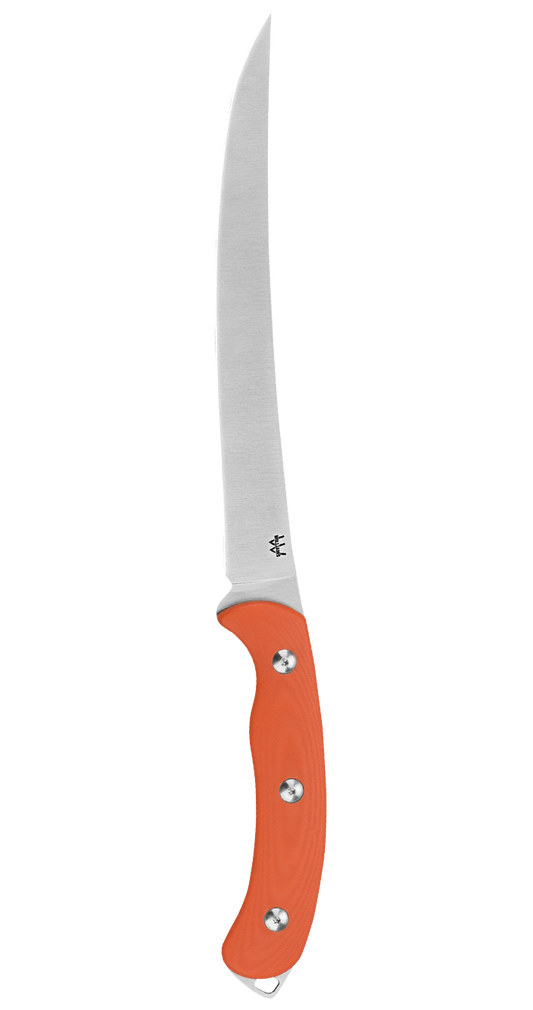

MM: What’s special about your knives? CW: I’m always careful answering that question, because I don’t want to come off as a braggart. But we put so much time and attention into these things before they even get pretty. The angles we grind at, the bevels on the cutting edge, the heat treatment, the steel we pick. It’s like the difference between a Kia and a Mercedes. They’ll both do the same job, but one has more time and energy put into it.

MM: How do you respond to sticker shock? CW: I actually don’t get that a lot. It’s more “Wow, these are beautiful but out of my price range.” Something handmade in the United States is obviously going to command a higher premium than something that’s thrown together overseas and sold in a big-box retailer. I don’t think consumers really need to be told that.

Try Williams’ Edisto knife (center) and oyster shucking will never be the same.

Try Williams’ Edisto knife (center) and oyster shucking will never be the same.

MM: Why does it matter that your knives are made in America? CW: When I was a banker I was always looking for top-quality stuff. As an outdoorsman, quality gear isn’t just necessary for success, it’s necessary for survival. In that area, American-made goods are top of the line. We use wood that comes from outside the United States because that’s where the trees grow. But all of our steel, all of our labor comes from the U.S.

MM: What’s your shop like? CW: It’s just a warehouse space with a small little office. There’s nothing glamorous about it. You can imagine that a knife shop is dusty, dirty and grimy. Keep in mind I’m also the janitor and everything else there. But I love it. I think I’ve found my purpose in life. You never know when the last knife order might come in, so I put all I can into each and every one.

MM: What’s a typical workday like? CW: There is no typical day for me. I might start out all excited about grinding blades all day and end up on the phone with a chef in Charlotte. We start the machines up before the sun comes up and shut them down after the sun goes down.

MM: What’s the process like when you design a knife? CW: Sometimes the light bulb just goes off on my head and I scribble it down on a napkin. Other times it’s a tried-and-true design that I think I can improve. All of my knives are named after the rivers and creeks in South Carolina. Some are pretty revolutionary, like my Edisto oyster knife. I was using a spade device to cut oysters and I noticed that it was like an arrowhead and I said to myself “That’s it. That’s what an oyster knife has to be.” It took me a couple years messing around with the shape, but everyone who gets them raves. Our tool helped a guy win the national amateur shucking contest, which is a little feather in our cap.

We can only hope the guy on the right recognizes how awesome the other guy’s knives are.

MM: Any advice for people who are thinking about throwing off their investment banking job and becoming craftsmen? CW: Well, it’s absolutely the best decision I’ve ever made in my life but also the scariest. I have two young children. Flying around all the time, missing basketball games and T-ball practice didn’t appeal to me anymore. The economics has worked out, but it’s less about making money and more about doing the best I can. I firmly believe that if you do what you love the money will follow. My grandfather always told me that if you love what you do you’ll never work a day in your life. Any time I feel a little down, I remember that. What I do isn’t really work. I feel like there are so many suppressed artists in a cubicle somewhere and in reality doing what you love is the American dream. I don’t know that knives are going to save the world, but we’re making people happy.

MM: What’s behind this resurgence of interest in American craftsmanship? CW: Well, the Internet makes it easier for people to conduct international business. Even five years ago that was a lot harder. That’s opened doors. But the biggest reason is, there are a lot of people who have had to circle the wagons and regroup and come up with new ways to make a living. There are a lot of people out there doing something that they weren’t doing before the downturn. The spark of creativity that lives within each of us has been fueled by a means of providing for your family. I think the American-made movement we’re in the midst of is something to behold, to say the least.

Read full article here